Our last field visit to rural Gujarat, where we took a closer look at grassroots resilience in the context of climate change, brought us face-to-face with the everyday realities of women-led cooperatives affiliated with the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) Federation. Through conversations with cooperative members, we witnessed how women are already adapting to climate stresses in intuitive, often unrecognised ways. The visit left us with more questions than answers, nudging us towards deeper engagement.

One question, in particular, set the tone for this visit:

‘Can cooperatives build tools to make everyday adaptation practices visible and valued within climate policy spaces?’

Upon closer examination, we began to understand that these institutions are not just enablers, but also stewards of women’s everyday responses to climate change.

This sparked a second question:

‘Can women’s lived responses — shaped within these cooperatives — be made legible not just to researchers, but to policymakers as well?’

What follows in this blog is a glimpse into the participatory tools that helped surface this everyday knowledge, grounded in the personal stories of women from the Kheda Women Farmers’ Collective — stories they shared with clarity, colour, and care.

On a sweltering May morning, the village of Govindnagar in Kheda district shimmered under a cerulean sky. The veranda of Ranjan ben’s home felt like an oasis — shaded and quiet — but alive with anticipation. Mats were neatly laid out on the floor, silently communicating a sense of oneness and welcome.

As we entered the open hall, Sharda ben — chirpy as ever — led us to the backyard along with Hansa ben. There, she proudly pointed to a newly installed Flexi Biogas unit, part of a pilot programme that SEWA is implementing in some villages.

By now, more women had begun streaming into the house. The volume of chatter grew, and their camaraderie was unmistakable. This was, after all, a space they usually held among themselves. When one of our male colleagues entered, a subtle shift occurred. Some women sat with a hint of hesitation — the kind that doesn’t speak, but settles in posture. But, as the day unfolded and chart papers, markers, and colour pencils were passed around, that hesitation dissolved into curiosity.

We sat down with the women to try out two simple, hands-on exercises: one where they mapped out their daily and seasonal routines as timelines, and another where they sketched a layout of their village as a map from their perceptions. These participatory rural appraisals were part of our ongoing journey with SEWA to understand how climate change shows up in their lives.

While drawing timelines and maps, the calloused hands revealed something striking: When adaptation is lived, it looks nothing like theory. It’s not captured in toolkits or indicator frameworks — it’s woven into the rhythm of survival.

Each sketch and each memory surfaced through these tools became a quiet act of making the invisible visible.

‘You forgot to mention how hard winter mornings are,’ one woman reminded another, sparking giggles. Summer was hot, but also labour. Monsoon was risk, but also the promise of renewal.

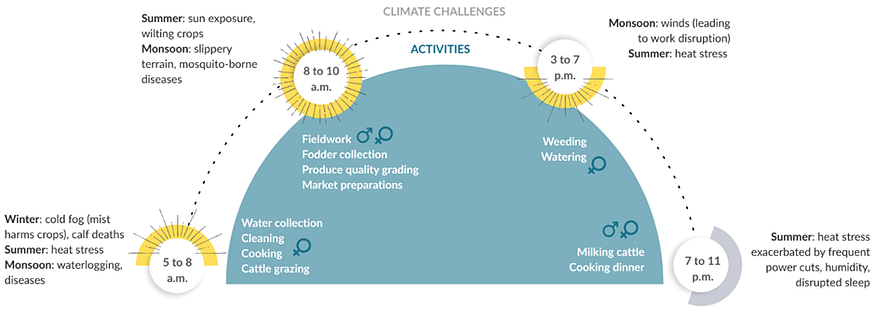

A snapshot from the daily/seasonal activity mapping revealed how deeply climate is intertwined with everyday routines.

The charts morphed into diaries, with lines crisscrossing between fields and homes, seasons and chores. Despite contributing equally to agriculture and dairy, women continue to shoulder the burden of unpaid domestic work, such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare. Time, for them, isn’t just an abstract measure; it’s a scarce and carefully rationed resource.

This tension surfaced even during the session. Some women grew visibly restless, aware of unfinished chores back home. Meanwhile, Sharda ben quietly beckoned us to the back of her house, eager to show us glimpses of her everyday life. With sparkling eyes and proud ownership, she showed us her kitchen, where chai bubbled on the biogas stove — her own small leap towards energy autonomy. Just beyond, neatly stacked stalks of freshly harvested bajra stood as another quiet testament to their collective labour.

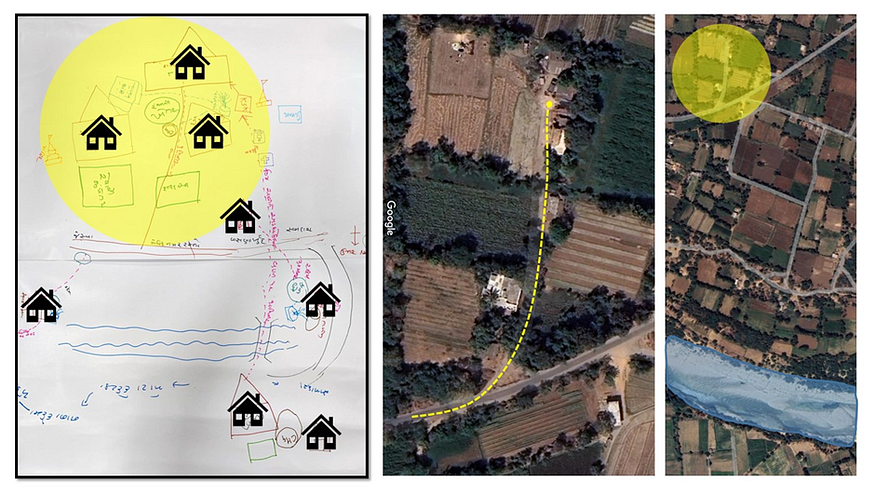

Parallelly, women were drawing a map of their village, marking homes, roads, cattle sheds, wells, and rivers — the everyday landmarks that shape their lives. As the map filled in, they began pointing out the long distances they walk each day, the spots they avoid during heavy rains or scorching afternoons, and the places where cattle often fall sick.

They also shared how the time of day shaped their exposure: afternoons in the open fields were unbearable in summer, while winter chores near water became almost painful.

We followed this with a sticker activity using simple symbols — cracked fields for drought, rising suns for heat, and flood waves for unseasonal rain. The women placed them not by data, but by what they remembered, what they felt, what they’d survived. Each sticker carried a story. This again nudged us to ask — what happens when such intuitive knowledge is taken seriously in policy?

By afternoon, the energy in the room had softened. Mats lay scattered, women sipped tea, savoury sev puffs were passed around, and conversations curled into quiet corners. Some leaned back against cool walls, others fanned their sarees like soft wings against the heat. That’s when Reva ben, quick-witted and perceptive beyond her sixty-odd years, posed a riddle:

Jo kharid kar laate hain, woh kabhi istemal nahi karte,

Jo istemal karte hain, woh usse dekh nahi sakte.

Batao kya hai?

(Those who buy it, never use it.

Those who use it, never see it.

What is it?)

There was laughter, confusion. Someone finally answered — a coffin. At first, we chuckled at the morbid punchline. But in the days that followed, the riddle stayed with us — not for what it revealed, but for what it suggested. To us, it felt like a quiet parable about extractive research: data collected by one, used by another, and never returned to those from whom it came.

SEWA reminded us of something fundamental: the people most affected by climate change are often the farthest from the decision-making process. The knowledge they share risks being buried in reports, locked behind paywalls, or repurposed for funder presentations — out of reach from the very communities it stems from.

Reva ben’s riddle reframed that reality for us. It brought us back to our original question:

‘Can women’s everyday adaptation practices gain visibility within the policy landscape?’

Through participatory tools that mine lived intelligence, we believe the answer is yes. But only if research becomes reciprocal. Only if cooperatives are recognised as archives of climate wisdom. And, only if women are seen not just as contributors, but as co-authors and decision-makers, as the voice of adaptation itself.

The authors work in the Adaptation and Risk Analysis group at the Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP), a research-based think tank.

More About Publication |

|

|---|---|

| Date | 10 July 2025 |

| Contributors | |

| Publisher | CSTEP |

| Related Areas | |

Get in touch with us at

cpe@cstep.in